In April 2022, Quebec's three main labor unions (CSN, FTQ, CSQ) announced the formation of a united front to tackle renegotiations of public-sector collective agreements which are expected to reach a new level of tension this fall. This is the eleventh in the province's history, the first having taken place 51 years ago, in 1972. At that time, the unions joined forces to put pressure on the province's largest employer, the government. The result: the biggest strike in Quebec's history and massive gains for workers.

Alexis Lafleur-Paiement, lecturer in philosophy at the Université de Montréal and a specialist in political ideas and institutions, explains. "At the end of the 1960s, the major central unions (the CSN, FTQ and CEQ) were well established in the public service and in several industrial sectors in Quebec. A perspective of confrontation with employers was held by several union leaders of the time."

In 1972, the workers' key demand was a minimum wage of $100 a week for public and parapublic sector employees (around $35,000 a year adjusted for 2023). At the time, roughly 50% of public sector workers earned less than this wage. For some employees, this represented a 40% pay rise.

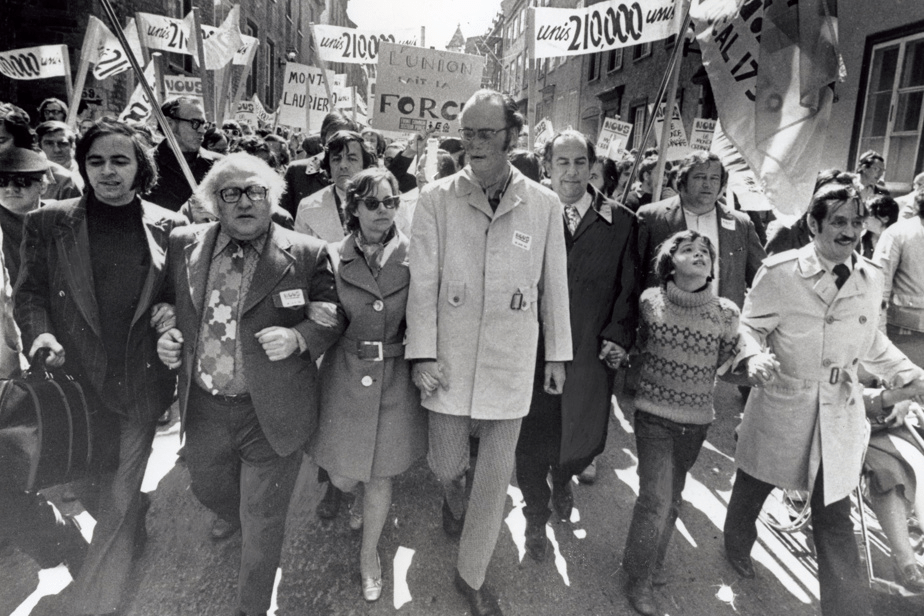

Negotiations stalled in March, and on April 11, 1972, 210,000 workers went on strike. Faced with this mobilization, Robert Bourrasa's government declared a special law to ban the strike, and imprisoned the three main union leaders for having called for the strike to continue. The strike quickly turned into a widespread social movement, gaining the support of a large part of the population. Demonstrations were organized across the province, as were numerous acts of civil disobedience.

In Sept-Iles, the workers went so far as to blockade the entire town. A huge assembly declared the closure of all non-essential businesses in the town, and subsequently took control of the roads, the local radio station and the airport. After clashes with the authorities, the strikers declared the city "under workers' control". Although the insurrection quickly came to an end, the pressure on the Quebec government was immense. Finally, in their new collective agreement, the workers win $100 a week plus a wage indexation clause.

Lafleur-Paiement adds that the 1972 common front had important repercussions outside the public and parapublic sectors. "Following the repression of the movement, a wildcat strike was called in May, involving many private industries [including Sept-Îles workers]. Private-sector workers thus benefited indirectly from gains in the public sector and were able to establish their own balance of power with their bosses."

"What you have to understand is that workers' gains in the public sector are generally beneficial for all workers. Indeed, since the government is the largest employer in Quebec, other employers tend to follow (at least in part) its standards so as not to lose their workforce, especially when unemployment is low."

According to Lafleur-Paiement, it was the unity and tenacity of the union movement that enabled such significant gains. Despite severe government repression, workers continued their strike, and dared to increase the pressure. It was this same fighting spirit that led to major gains during the second common front, in 1975-76.

"In 1976, public sector workers won wage increases, more paid vacations and equal pay for men and women. These gains had an impact on the conditions of private-sector workers, as bosses had to adjust if they didn't want to lose their employees to the public sector."

- Us Against the State: A Documentary on the United Front

- Quebec healthcare workers still without a contract

- Quebec unionized nurses reject “disrespectful” proposed deal

- “We could have fought together for better,” says FIQ member

- One in ten workers soon on strike?

- Privatization in the name of “efficiency”

- Strike mandates accumulate with overwhelming support

- An Education Reform Deaf to the Key Issues

- Québec government improvises solutions

- 1972, the Year Workers Shook the State

- 100,000 workers in the street: “they’ve had enough”

- It’s Halloween for Quebec’s Public Employees, Or at Least for Some

- United Front workers determined to keep up the fight

- FAE to call unlimited strike on November 23

- A historic movement, “we’ve never seen anything like it”

- The CAQ cares about kids (or so it says)

- Government treatment fuels “our indignation and will strengthen our mobilization”

- Superior Court Violates Teachers’ Right to Strike

- “Legault and all the others are destroying Quebec as we know it”