The Tribunal administratif du logement (TAL)'s administrative offices and courtrooms occupy 30 buildings across the province. Many of them are owned by private landlords and real estate investment trusts (REITs) that also own residential properties, making them vulnerable to conflicts of interest.As the government agency responsible for for handling disputes between tenants and landlords in Quebec, the TAL handles over 70,000 cases a year on issues such as rent increases, evictions, and urgent repairs.

Many of the tenants at 135 Sherbrooke East in Montreal are no stranger to TAL hearings. Their landlord, CAPREIT, demands rent increases for every tenant, every year. In 2022, members of the building's tenants' committee began a campaign to deal with the unreasonable rent hikes. They conducted a survey to inform their neighbours about disparities in rent rates across the building and distributed information about the legal right to refuse rent increases, along with copies of the forms necessary to do so.

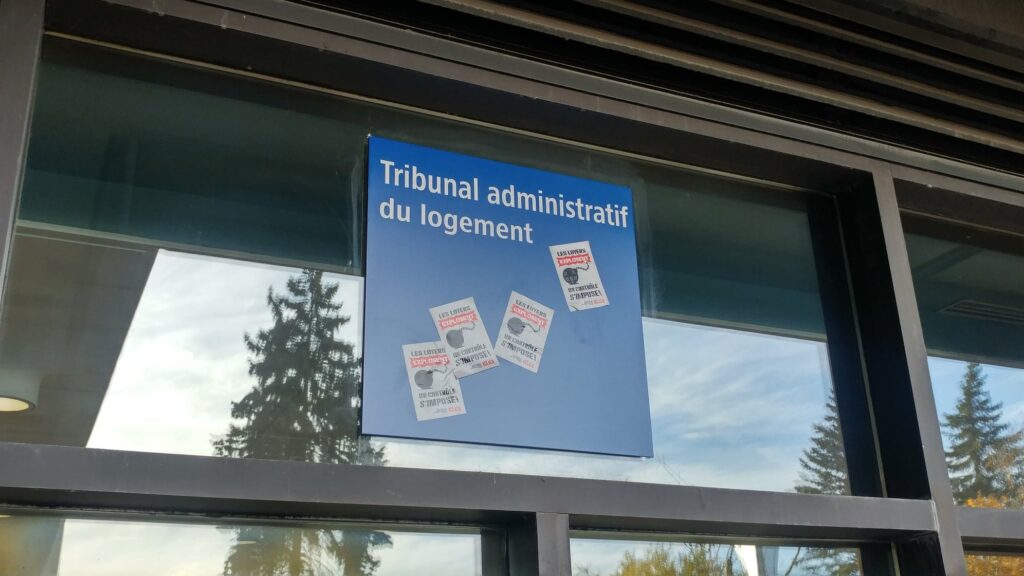

"CAPREIT flatly refuses to negotiate now," one tenant told the North Star. "The only thing to do is refuse and let them take you to the Tribunal." TAL hearings in this part of the city typically take place at the TAL offices in Olympic Park. Upon arriving at the complex that contains the TAL offices, tenants are directed through the large complex by signs which bear the name of their own landlord: CAPREIT.

To realize that one's own residential landlord also owns the government office that will ultimately decide how much rent that landlord can extract from tenants is bitterly ironic. It's also perplexing, given that CAPREIT bills itself as a residential landlord. The property listings on its website include only apartments and mobile home parks, but among CAPREIT's $17 billion in assets is the TAL building in Olympic Park where thousands of cases against it are heard.

A North Star investigation found that half of TAL offices in the province were owned by private landlords and REITs. Of these, two-thirds were owned by landlords who also owned rental housing or other residential real estate. Some are owned by large concerns that own residential housing directly, like Ontario-based CAPREIT, Nova Scotia-based Crombie REIT and Montreal-based Stanford Properties Group, which rent to the TAL in Montreal, Baie-Comeau and Joliette respectively. Others are owned by smaller residential landlords and by holding companies whose primary shareholders are housing developers or real estate brokers.

Of the 28 TAL buildings for which such information was publicly available, only half are owned publicly, a trend that is likely to continue as governments sell off public assets. The TAL is far from being the only government agency in the province which rents office space from private landlords. The Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CNESST), the government organization responsible for enforcing Quebec's labour laws, reports that 30 of its offices are rented from private landlords such as Beauward Immobilier, which rents to the CNESST in Joliette as well as to the TAL in Saint-Hyacinthe.

It is impossible to say conclusively whether the ownership of TAL buildings by residential landlords has a direct effect on the integrity of the judges who decide the fates of millions of renters in Quebec, the province with the lowest rate of home ownership in the country. It certainly, however, creates at least the appearance of a conflict of interest. If a case was before the courts in which the judge's personal residential landlord was one of the parties, that judge would be quickly replaced in the interest of fairness.

Yet when the compromised party is not a particular judge but the TAL itself, it is simply business as usual. The very structure of our economy, in which so much land and so many buildings are in the hands of a small handful of wealthy owners, means that tenants, workers or anyone else seeking justice in a dispute with the economic elites who hold power over them must often pursue it in a venue which is owned by people who have a material interest in taking advantage of tenants and workers.

And this is true whether the landlord of the TAL building in which your case is being heard owns residential properties as well or only commercial ones. For the tenants at 135 Sherbrooke East, the fact that their rent increases are set year after year in a courtroom owned by CAPREIT is simply the cherry on a very peculiar cake.

- CAPREIT extracts as much money as possible from their tenants

- A Law Written for and by Landlords

- The Legault Government Launches an Attack on Tenants

- A Campaign for a Moratorium on Evictions

- When Politics and Business Violate Tenants’ rights

- Real estate developers reinforce shortage by reducing housing starts

- What effects will the adoption of Québec’s Bill 31 have?

- Housing bill continues to be denounced by unions and housing groups

- Conflict of interest for Quebec’s tenant-landlord tribunal?

- One year later, tenants still standing up to excessive rent increases

- Developers paying pennies to bypass affordable housing requirements in Montréal

- Build, but at what cost to tenants?

- A First Victory for Quebec Tenants Against the CAQ

- “Montreal attacks the homeless instead of homelessness”