Across Canada, the various levels of government seem to agree that a lot of new housing needs to be built, and fast. In Quebec, however, the suspension of the By-law For A Diverse Metropolis and the adoption of the Construction Reform Law (Bill 16), which follow from this logic, could have negative repercussions for tenants, according to several experts.

Indeed, the massive construction of new housing will certainly have an upward impact on rental costs. In Quebec, rents for new housing are not subject to any restrictions in terms of increases in the 5 years following their arrival on the market, and this is not an isolated case in the country.

In Manitoba, new constructions are exempt from restrictions on increases for 20 years; in Ontario, the first lease signed after the construction of a building is subject to no restrictions on increases.

This type of settlement tends to exacerbate an already worrying situation. According to Statistics Canada, by 2021, more than a third of renter households in Quebec will be spending more than 30% of their income on housing costs. Since then, rents have risen by around 40% in the province.

So, according to François Saillant, former spokesman for the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain (FRAPRU), contacted by Étoile du Nord, the political class is on the wrong track.

“They say that if the market eases, which is far from being the case, the crisis will subside. But even if the market does ease, that doesn’t mean that rent increases will stop, that the cost of housing will go down. For me, that’s not the solution.”

François Saillant explains that a lot of housing was built in the decade from 2010, and “that’s when the rise in rents started. Construction had more of an effect of pulling up rents than of contributing to lower increases.”

Indeed, a large proportion of the housing units that have been built recently or will be built in the near future are intended for sale or rent to wealthy or affluent individuals. Tenants’ organizations are calling for a moratorium on the construction of luxury condos.

On the other hand, when looking at the major housing projects planned in Canada, for example in Greater Montreal, there very little room for non-market or rent-controlled housing.

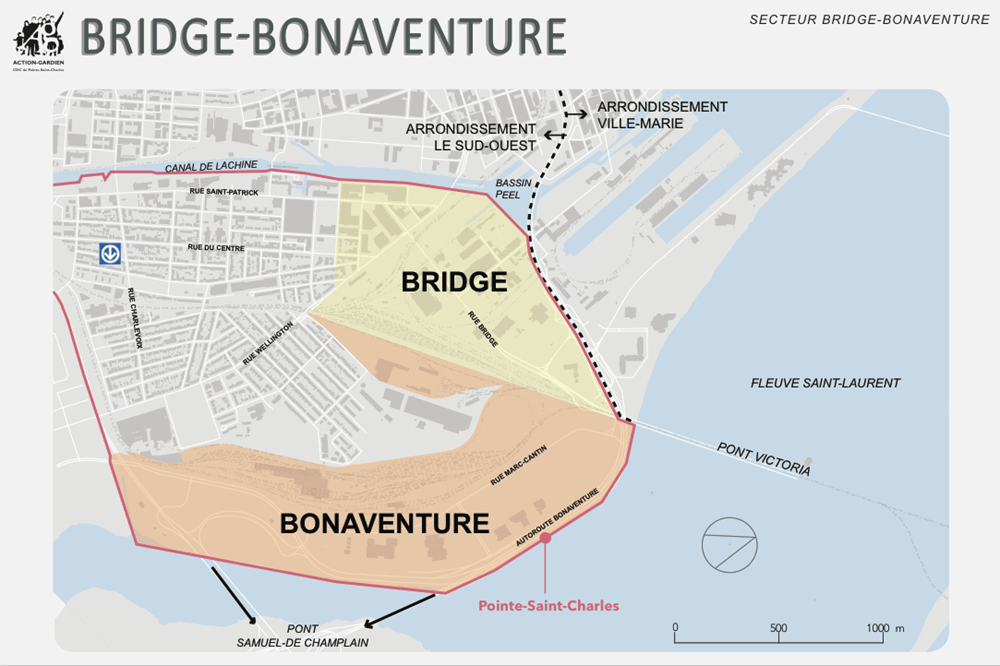

The City of Montreal, in partnership with the Board of Trade of Metropolitan Montreal, plans to build 15,000 new housing units in the Bridge-Bonaventure area by the end of the decade. Of these 15,000 units, there’s no way of knowing how many will be social or affordable housing.

For François Saillant, these are real estate projects that do not meet the population’s crying needs.

“In the case of Bridge-Bonaventure,” he explains, “there were public consultations led by the Action Gardien neighborhood group, which took the population’s pulse on what they wanted in terms of development.”

“Their message was: we don’t want a second Griffintown. But that’s what’s likely to happen here. I looked at the plans, and it looks a lot like a new Griffintown. So we haven’t been listening to the needs of the neighborhood.”

Saillant also points to the lack of solutions proposed for regional cities. “There isn’t an urban center today where the vacancy rate is higher than 2%, whereas the so-called equilibrium rate is 3%.”

In an attempt to speed up construction, the CAQ is proposing a range of measures for the industry, including imposing greater mobility on workers to build more in the regions. Its Bill 16 plans to allow any contractor to move its workforce throughout Quebec.

But the task is so daunting that Saillant is skeptical about the impact of such a measure. “I don’t think it will have any impact, or only an extremely minor one. No matter how much we move workers around, there’s a shortage of housing everywhere.”

Saillant also has concerns about the quality of new construction following the passage of Bill 16.

“I have my doubts about the longer-term quality of new housing. The pressure to build housing at any cost, as quickly as possible, can result in very poor quality housing, and at some point, the people who will have access to this housing will be penalized.”

Rather than making wholesale changes to building laws and municipal bylaws to make them more attractive to the private sector, Saillant maintains that the solution to the crisis lies in minimizing the role of the market and monopolies.

“It’s a systemic crisis linked to the desire to make money, to make a profit, to increase investment fund returns. The whole system, the whole housing market, is contaminated, if you like.

This move away from a market logic around housing, defended by Saillant, is taking place at the planning level of some socialized housing projects, but the construction sector largely escapes it.

“There are not-for-profit players in several fields who are involved. But construction itself, unfortunately, has never developed anything on that front, and for me, that’s one of the big shortcomings we have.”