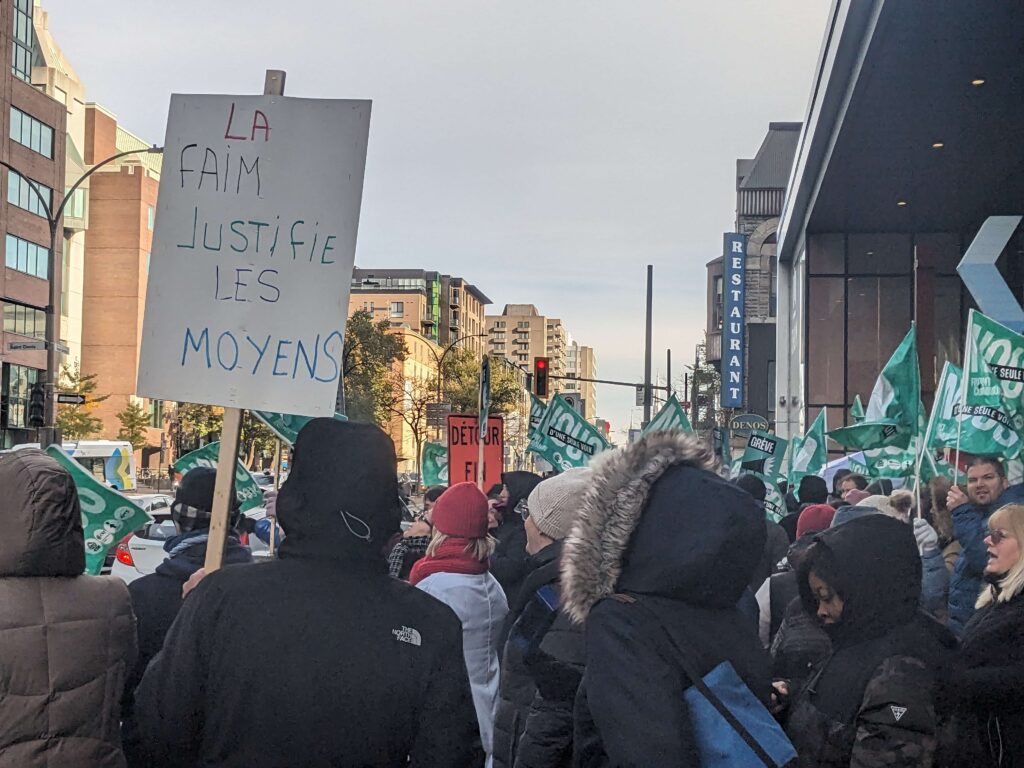

If you thought labour unrest would slow down after the agitation of 2023, think again. Between strikes, back-to-work orders and panicked bosses, workers proved they were far from having said their last word. Here’s a rundown of 2024, a year full of action.

In 2024, as in 2023, there were over 700 work stoppages due to conflicts such as strikes and lockouts. Since 2010, these have been the two most turbulent years in the labour movement. By way of comparison, the third most active year for labour disputes in Canada was 2012, with 281. Inflation and poor collective bargaining during the pandemic left workers much poorer, so they’re trying to make up for it.

However, the state has got in the unions’ way, with its tendency to intervene more and more on behalf of employers, when it is not the employer itself. On the railways, in the ports and among postal workers, we have seen the federal or provincial governments intervene to diminish the effects of strikes, or even to outlaw them. In the public sector, it is above all the threat of back-to-work legislation taking away the right to strike that has demoralized unions and led them to sign cut-rate agreements without putting up much of a fight.

Public sector

By December 2023, tensions were at their highest between the government and the Common Front of the Québec public service, which included 420,000 unionized workers. Many wondered whether this confrontation would explode into open conflict with an unlimited general strike. However, an agreement in principle reached on the eve of the new year put out the fire in February. The union members adopted it.

In April, members of the FIQ, which mainly represents nurses, voted overwhelmingly against an agreement in principle. They finally accepted an offer from the conciliator in the fall. Acting solo, Quebec nurses did not attempt to strike throughout 2024. The FIQ threatened to stop overtime as early as September 19, but the Tribunal administratif du travail forced it to abandon this pressure tactic, deemed illegal.

In Nova Scotia, 10,000 teachers reached an agreement after threatening to strike. Ontario college teachers (15,000 members) are trying to do the same, after taking out a strike mandate in November. They want to benefit from improvements in their conditions thanks to the billion-dollar surplus generated by the colleges last year.

New Brunswick nurses, in negotiations all year, rejected a collective agreement by a majority vote in September, before finally reaching an agreement in December. It would give them each a bonus theoretically worth up to $10,000. CUPE nurses (around 1,600), however, refuse to sign until the government withdraws a 2013 anti-union law that weakens their pension fund.

Manitoba’s 25,000 lowest-ranking health-care workers, for their part, won an average gain of 27% over four years (6.75%/year). They were preparing to go on strike, but the employer finally gave up and proposed an agreement satisfactory to them.

Hotels

With the pandemic crisis and its ravages on the tourism industry receding further and further into the distance, hotel workers have regained some bite in their fight for better working conditions. During their last negotiations, many unions had to contend with the declining profits of the major hotel chains. Today, those profits are steadily rising. One Marriott union demonstrated that room rates have risen by over 100% since the end of the pandemic.

In Vancouver, Holiday Inn and Suites, Hyatt Regency and Residence Inn went on strike during the year. The Sheraton Hotel, which had been on strike for 14 months, declared victory after a dispute involving the use of scabs. The Radisson Blu Hotel, meanwhile, is in its third year of strike action, and here too, scabs are being used. The strike at the Radisson Blu Hotel began with the dismissal of 143 workers. These strikes have been accompanied by boycotts, one of which was called by Richmond town hall.

In Quebec, 31 unions affiliated to the CSN joined forces for negotiations in the hotel industry, initially putting forward an ambitious demand for a 36% wage increase over 4 years. The majority of unions, however, folded and decided to settle for 21% over 4 years. The unions seem to have abandoned their objective of making up for the losses they incurred as a result of the agreements made with management during the pandemic (2% per year, while inflation was approaching 7% in 2022).

This coordinated mobilization led to a one-day strike in August, when 2,600 people stopped work at the same time. Some ten hotels have still not signed an agreement with their employer. The Comfort Inn employees in Baie-Comeau, who are affiliated to the Steelworkers, have been on an unlimited general strike since March 22.

Longshoremen

The year 2024 was marked by numerous labour disputes in the ports. On October 1, all the major ports on North America’s east coast, with the exception of Mexico, were on strike or locked out (Quebec, Montreal and 36 U.S. ports).

In British Columbia, tensions had already been brewing since 2023, but this year it was the grain elevator longshoremen who went on strike for four days in September. Employers cried out for government intervention, and eventually won their case. Employers declared a lockout against the longshoremen on November 4, before the state forced them back to work 10 days later.

In Montreal, following unlimited partial strikes at Termont terminals, the Port of Montreal employers’ cartel declared a lockout on November 10. Six days later, the government forced the longshoremen back to work.

At the Port of Quebec, the lock-out had begun long before those in Vancouver and Montreal. By November, it had reached its 28th month, almost 800 days. However, the Canadian government forced the dockworkers back to work on November 12, taking the wind out of the union’s sails, which had been holding out for over two years.

The port operated at least minimally thanks to the sustained work of strikebreakers. Despite a federal law passed this year, in particular following pressure from Quebec longshoremen, the scabs had free rein until June 2025, when the law was actually applied.

Trains

The same approach was used by the rail industry to avoid a strike that would temporarily reduce their profitability.

Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Kansas City workers had wanted to strike in May, but the Canadian government had forced them to delay their pressure tactics, thus allowing their strike mandate to expire. The second strike attempt was met with a lockout by the employer, followed less than 24 hours later by state intervention forcing the workers back to work.

Canada Post

The 55,000 postal workers went on strike in mid-November, ending in mid-December. Under constant attack from the mainstream media and their employer, the workers multiplied visibility stunts. Finally, the government used the same article 107 as for the ports and railways to bring the labour dispute to a premature end.

However, instead of imposing arbitration, the government asked a commissioner to investigate the corporation’s labour relations and business model. His recommendations are due in mid-May, and the collective agreement has been extended until May 22. Postal workers will regain the right to strike on that date.

Passenger transportation

Quebec school bus drivers fought hard during 2024 to ensure that the $122 million given to school bus companies by Premier François Legault would also be used to improve their working conditions. Several unions won increases approaching 10% per year. For example, a Teamsters union won a 67% increase over 6 years.

In 2023 and 2024, 19 CSN bus unions went on strike, out of a total of 32 negotiations. Three unions from companies belonging to Groupe Gaudreault are still on strike: the Syndicat des chauffeurs d’autobus de Brissette & Frères, the Syndicat des travailleuses et travailleurs de Transcollin and the Syndicat des travailleuses et travailleurs des Autobus Gaudreault.

A hundred Sault Ste. Marie school bus drivers received just under a 5% annual wage increase in January. In July, 90 drivers at the Seine River School Division in Manitoba won a new collective agreement after rejecting a first agreement and threatening to strike.

Not all bus drivers, however, negotiated good agreements. For example, employees in Alberta’s Prairie Land School Division won wage increases of less than 2% a year.

The bus drivers of public transport companies were not to be outdone. While there were no unlimited general strikes this year, unions resorted to them on an occasional basis, but also as a threat.

In Sherbrooke, Quebec, workers went on strike for 4 days in September. STS employees are divided into 4 unions according to trade, but they are united for the 2024 negotiations. It remains to be seen whether this union’s struggle will resonate with the upcoming negotiations of other workers in Quebec, such as STM mechanics.

In Toronto, a transit strike was scheduled for June 7, but a last-minute agreement averted it. This gave employees a 13% increase over 3 years.

In the same province, in Guelph, workers also won a good contract after brandishing the weapon of strike action, securing an agreement less than two days before the scheduled work stoppage. In negotiations since March 31, Brampton’s blue-collar workers, including transit employees, went on strike for one day in early November.

In British Columbia, the 150 or so supervisors of Coast Mountain Bus (which operates Vancouver’s public transit buses) threatened a partial paralysis of public transit in this major city at the beginning of the year. However, an agreement was reached on February 1, the day before their planned strike.

In Kootenay, British Columbia, ferries have been on strike since November 3, when the government forced the union to operate three ferries a day despite the strike. Without a contract since April 1, Quebec employees on the Matane-Baie-Comeau-Godbout ferry and the Quebec-Lévis ferry have gone on strike for a dozen days this year, including a sequence during the construction vacations that put pressure on the tourism industry. Mechanical and navigation officers also went on strike in June, paralyzing ferries serving Quebec City, Lévis, Sorel-Tracy and Matane.

In aviation, where strikes are relatively rare, the workers essential to the smooth running of flights have also taken advantage of their strategic role to put pressure on their employer. Air Canada pilots’ high-profile strike threat led to 42% pay gains over 4 years.

At Air Transat, it was the flight attendants who threatened to strike this year to improve their conditions. The 2,100 employees rejected two tentative agreements in January, before finally voting 63% in favor of an agreement in February that gave them a 6% annual pay rise, plus improved vacations and vacation entitlements.

Parapublic

In both Quebec and Ontario, provincial government liquor store employee unions were particularly concerned about casual and part-time workers in this year’s negotiations. These represent 70% of SAQ and LCBO employees.

The LCBO union in Ontario added to its demands the maintenance of clauses in its collective agreement that limit the privatization of alcohol sales, and at the same time guarantee job stability for its members. Union members ratified an agreement with their employer at the end of July, after 2 weeks on strike.

SAQ employees in Quebec ratified an agreement in December after more than a year of negotiations. During this period, they staged a number of stunts, including an occupation of the Palais des Congrès in April and five one-day “surprise strikes”.

Another state-owned company: Hydro-Québec is currently negotiating with several unions at once. This year, the campaign against electricity privatization was the main focus of these unions, but during the autumn, the tone hardened and several strike mandates were voted. Specialists and Professionals (CUPE 4250), Office and Professional Technicians (CUPE 2000), Network Employees (CUPE 5735) and Site Nurses (CUPE 5514) all voted for similar mandates, representing almost 8,000 workers.

Be part of the conversation!

Only subscribers can comment. Subscribe to The North Star to join the conversation under our articles with our journalists and fellow community members. If you’re already subscribed, log in.