A Montreal tenants' advocacy organization is raising concerns about plans for luxury development on the site of the city's former Molson brewery. The North Star spoke with Léandre Plouffe, an organizer with a housing committee in east-end Montreal, BAILS, located in Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve (MHM).

In mid-December, real estate developers announced plans to develop 5,000 housing units on the site in the Ville-Marie district. But the borough ranks first in Montreal's poverty index. Nearly one household in five has to spend 80% or more of its income on housing. The district is also home to a significant portion of Montreal's homeless population.

For Léandre Plouffe, the creation of this new district risks leading to the expulsion of the borough's working classes.

“The plan is to attract more tourists, that's what the developer of the Molson District says. They're trying to attract more rich people to Montreal's inner city. This is some kind of big, big, accelerated plan for major transformation of the city. It's not democratic, and it's not what we need.”

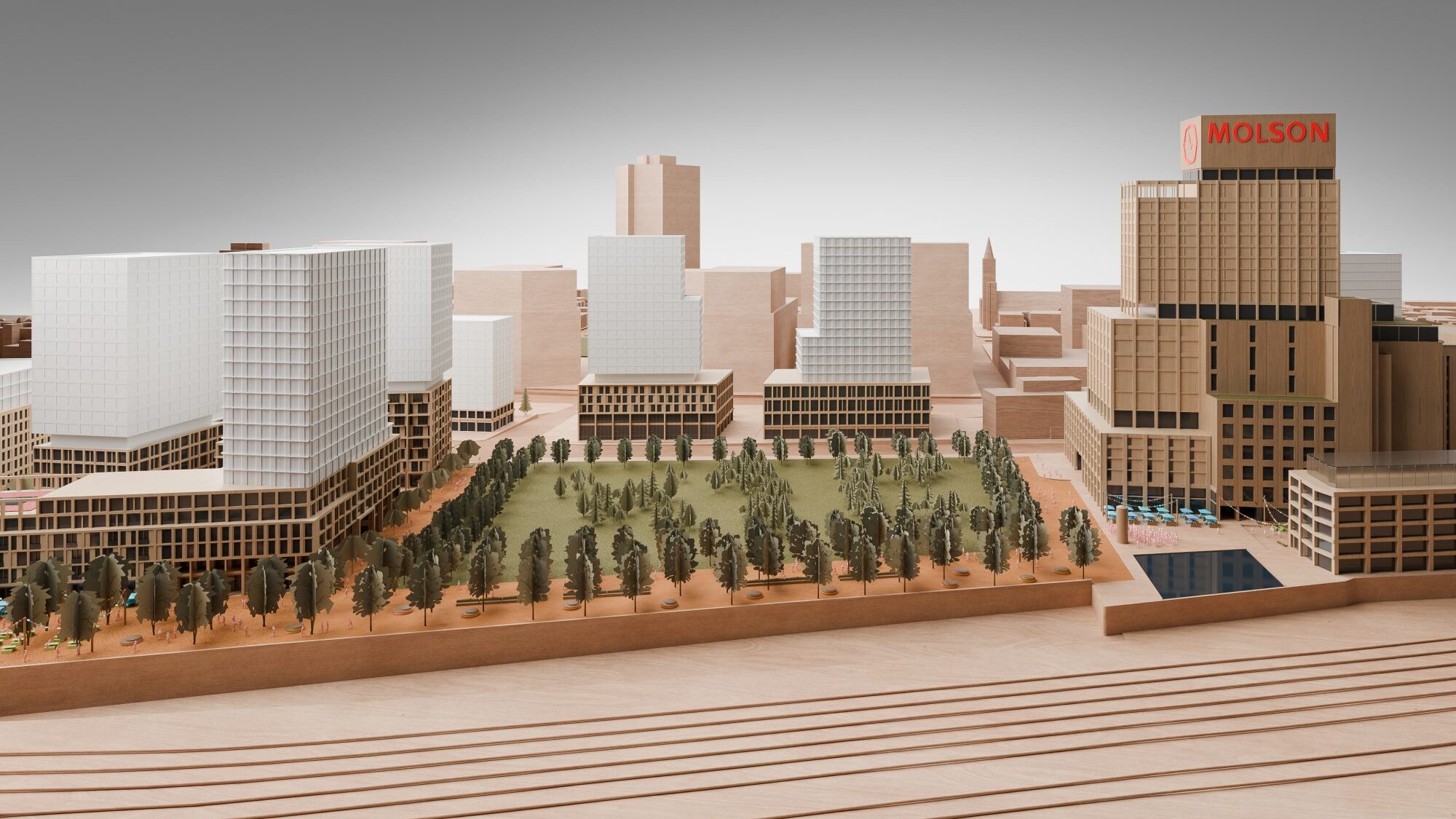

The Montoni Group, which is behind the brewery district project, says it wants to build offices (for which vacancy rates have shot up to 17.9% in Montreal since 2020), residential buildings, shops, and a hotel on the site.

According to Plouffe, the plan misses the mark. “What we're doing is responding to the artificially created needs of the business class, the creative class, the nouveau riche, and people from out of town to attract them here. The businesses and services developed in the area will respond to their needs, not those of less affluent residents.”

There is also a growing need for local services in the neighbourhood. Last year, the Centre de services scolaires de Montréal evicted eight community organizations (including a daycare, a food bank, and the BAILS committee) from one of its buildings to take over the premises.

However, the plan for the Molson district does not include any schools, public daycares or local health clinics. With the development of the future Quartier des lumières on the site of the former Radio-Canada Tower, next to the Molson brewery, demand for these services is likely to explode.

If local services are created, they'll likely be privately run, points out the BAILS committee organizer. “It's bound to be expensive, private services for the rich people moving into the new buildings to get their kids looked after, to get an education, care, and so on,” he says. “That's my fear.”

For Léandre, the problem lies with profit-driven real estate development. “We need to point the finger at the oligarchy, that is to say, a handful of extremely wealthy people who hoard enough wealth to start weighing in on municipal territory development and city planning.”

Léandre Plouffe also deplores the absence of any real public consultation on the development of real estate in the area. “Just going and asking questions in the borough, here in Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, has been made difficult. If we don't follow decorum to a tee, they take us out with the police, and we have no recourse.”

A citizen of the borough was expelled from the borough council by Mayor Pierre-Lessard Blais last month. Ligue 33, another MHM neighbourhood organization, had denounced this action on Facebook, after they too had been expelled from the council.

According to them, the citizen asked the mayor to “stop avoiding her questions and answer them seriously.” She was then allegedly detained by police for over fifteen minutes. In the publication, Ligue 33 “condemns these despotic actions. Under Projet Montréal, MHM has started looking like a banana republic, with a leader who despises the population and represses anyone that tries to ask questions and point out the flaws in their plans.”

Mr. Plouffe explains that everyone involved in the neighbourhood has been pleading for years for more social housing and solutions to the housing crisis. “But the result is that we're going to build a new affluent neighbourhood downtown.”

In his view, new ways of dealing with the phenomenon are needed. “There are people who have been on social housing waitlists for 10–20 years. So, in the short term, we're going to have to think about new strategies to counter these phenomena. They're weakening the neighbourhood's entire population, its most vulnerable residents most of all.”