Following the announcement of Labor Minister Jean Boulet’s Bill 89 (PL89), some unions and organizations criticized the CAQ for drawing inspiration from the Duplessis government. Union Nationale, Duplessis’s party, vehemently opposed any attempt to organize the working class. During this period, strikes were illegal and violently repressed.

To better understand what has changed since then and how workers were able to gain recognition for their right to strike, The North Star spoke to Alexis Lafleur-Paiement, a doctoral student in political philosophy and lecturer at the Université de Montréal. He specializes in political institutions and social conflict.

For Lafleur-Paiement, one thing is clear: repressive measures like PL89 are nothing new.

“Since the beginnings of capitalism, corporations and the State have used every means at their disposal to repress workers. This includes special laws, government decrees, fines, arrests, various anti-union strategies, the use of scabs and even relocation.”

In his view, what is changing is simply the form these attacks take:

“Before, the State could directly imprison its employees who went on strike; now, it has to impose a special law before proceeding with repression. In the private sector, new legislation has reduced physical violence against workers, but we still see repression, dismissals, the use of scabs, et cetera.”

Lafleur-Paiement also draws a clear link between workers’ combativeness and the state’s recognition of their rights.

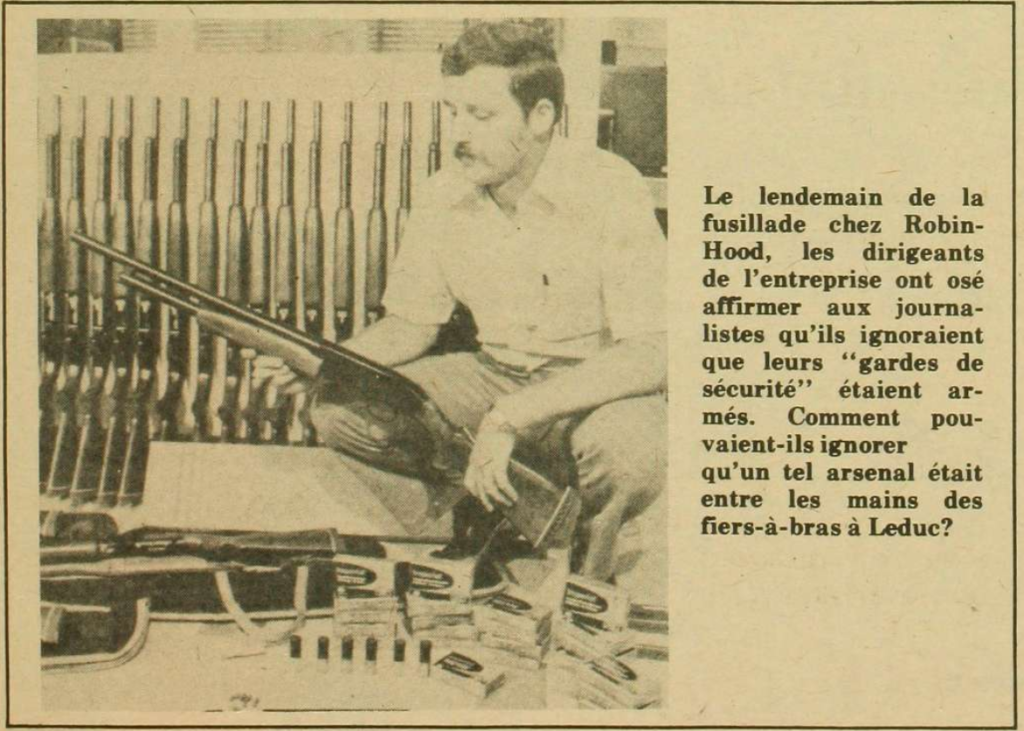

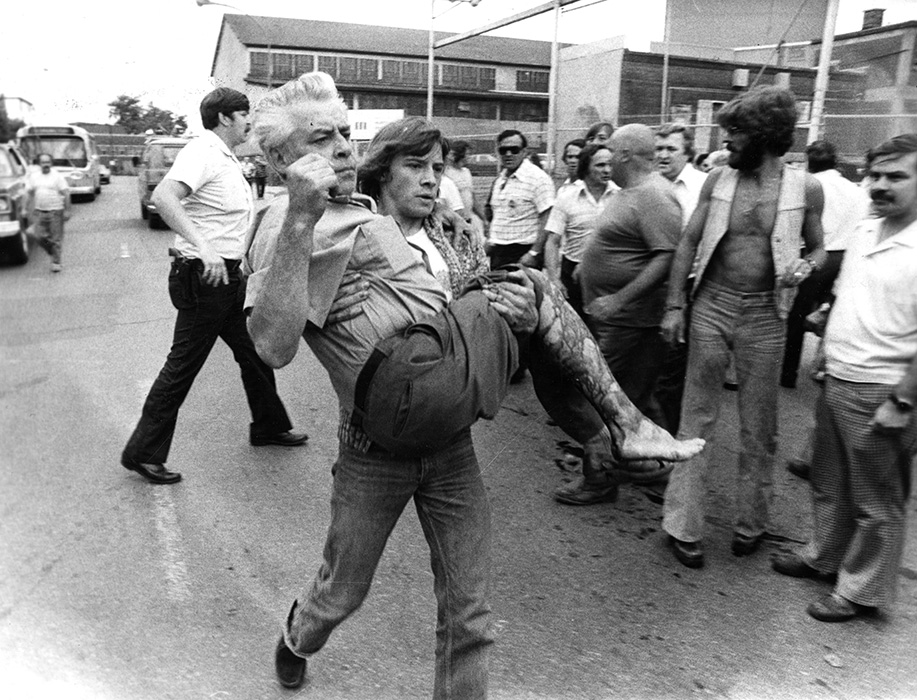

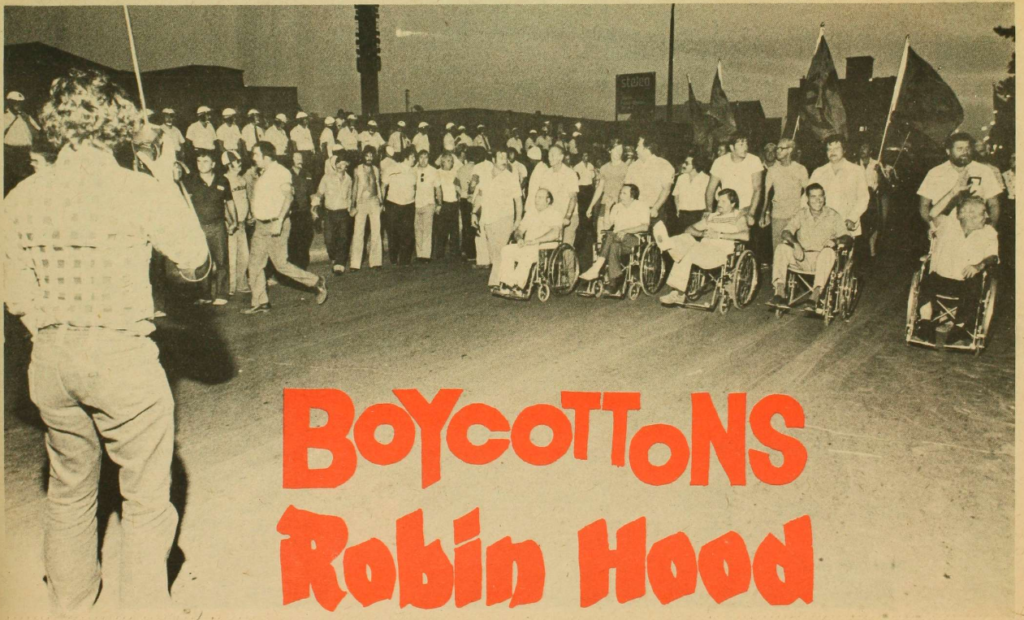

“We can see that the gains concerning the right of association and the right to strike correspond to the moments of the strongest workers’ struggles (the 1870s, the 1930s and the 1970s). It was the determination of workers during several conflicts in the 1970s, going as far as confrontation with corporate militias as at Robin Hood in 1977, that forced the adoption of anti-scab legislation.”

“More recently, it was the Saskatchewan employees’ fight that led to a Supreme Court of Canada ruling in 2015, which consolidates the right to strike and is now authoritative across the country.”

He explains that the laws passed by federal and provincial governments are sometimes meagre compromises when compared to workers’ demands.

“It wasn’t until 1934 that the federal government recognized the right to picket to inform the population of the reasons for a work stoppage. The ban on the use of scabs dates back to 1977, following repeated requests from workers. But all these rights are relative, since governments can still intervene at will to regulate or put an end to a labour dispute.”

The academic adds that framing the right to strike also limits the actions to which unions can legally resort. “The times when strikes are called are now regulated (only when collective agreements have expired), and the way conflict is brought to an end is more predictable (negotiation framed by the Labour Code).”

“Labour disputes take place in more predictable forms, but not necessarily better for employees. It is only workers’ determination, unity and fighting spirit that can guarantee them gains.”

For the social conflict specialist, the more organized workers are, the more combative and determined they are. “The most intense moments in terms of labour conflicts correspond to periods of development of workers’ organizations, for example the 1870s with the Knights of Labour, the 1930s with the rise of the Communists, or the 1970s.”

He adds that the organizing of workers must be accompanied by efforts to build unity and politicization through workers’ struggles if they are to yield results.

“This period (the ’70s) corresponds to a radicalization and collaboration of Quebec’s central labour bodies, resulting in the highest strike rate in the province’s history. Today, we’re also living through a period of repoliticization of the labour movement, with an increase in strikes.”