Quebec’s labour tribunal (TAT) has suspended the right to strike of 2,400 STM support employees, who were set to begin a general strike last Sunday to revive stalled negotiations. On May 23, the TAT ruled their essential services plan insufficient. The Montreal Transport Union plans to issue a second strike notice soon.

The TAT acknowledged that a strike can and must cause inconvenience. It adds that it “must distinguish these inconveniences from the danger to public health or safety caused by the strike […] This danger must be real in fact; mere fears or apprehensions are not enough to neutralize or reduce the right to strike.”

Administrative judge Sylvain Gagnon then justified the danger he perceives in a surprising way, writing that “a complete shutdown of the metro […] will lead to crowds gathering around metro stations and bus stops, causing overflow onto public streets, altercations, and aggressive behaviour […].”

The 39-page document offers little evidence of a real danger to the public. It also fails to explain why organizational adjustments wouldn’t suffice. It cites the closure of Saint-Michel station, which caused crowds, some aggression and headaches for overtime constables. It also mentions a few assaults on drivers during reorganizations. In 2023, 348 assaults were reported, but according to the president of CUPE 1983, these mostly reflect the state of society, not the transit system.

The text claims that ensuring safety during a strike would be impossible. Yet it does not seriously consider reinforcements from other SPVM units or better internal organization. Moreover, the strike had been announced nearly a month in advance to give the STM time to prepare.

More cuts and rollbacks

Three major STM unions are negotiating to renew their collective agreements, which expired at the start of the year. They demand wage catch-ups and better work-life balance conditions to slow the exodus to the private sector and the rise of subcontracting.

On the employer side, management wants to impose difficult evening, night and weekend shifts, relocate personnel and increase private subcontracting—particularly by privatizing adapted transport.

These attacks do not sit well with Bruno Jeannotte, president of the Montreal Transport Union. “The challenges facing the STM are too big to alienate maintenance workers. If we want to maintain our infrastructure and implement electrification, we must rely on our expertise, not subcontracting.”

Infrastructure problems and service breakdowns are worsening across the metro and bus network. In May, it was revealed that half of metro stations are in very poor condition. Last year, Saint-Michel station had to close for weeks due to major repairs.

In its latest budget, the CAQ government cut over $250 million from STM’s asset maintenance budget. Yet, this department is responsible for repairing and maintaining the network’s infrastructure.

For Benoît Tessier of the Office and Professional Employees Union (SEBP 610), these austerity measures show government interference in the negotiations. “The government is basically warning STM by saying, ‘I expect you to get rollbacks in collective agreements before you come back asking me for money. Privatize, cut working conditions, and then come ask for money.’”

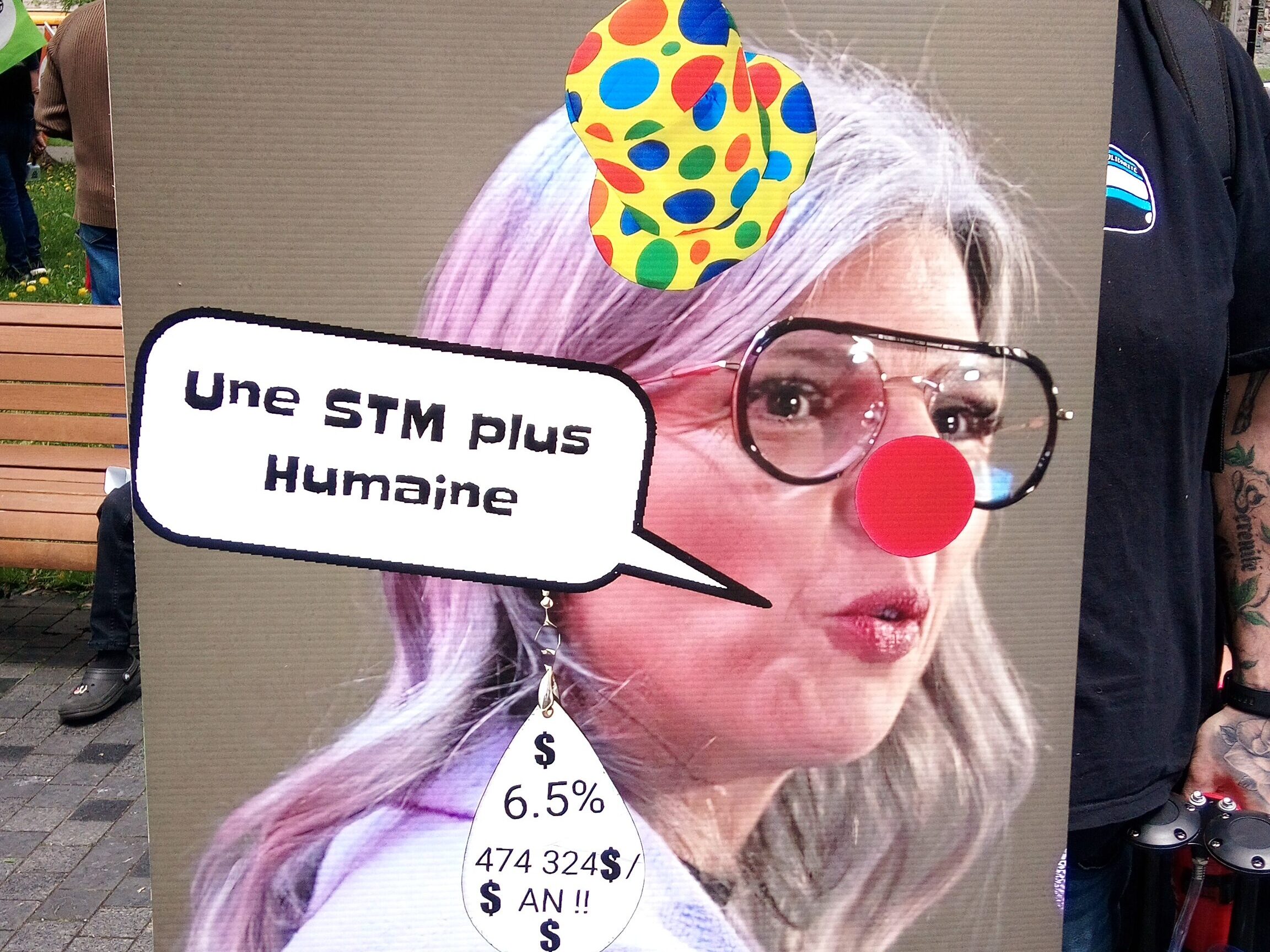

While pushing budget cuts on the workers who keep the network running, STM’s board of directors voted a 6.5% annual raise for its CEO. Her salary will increase from $446,000 to $474,000.

On May 25, 500 STM workers gathered in front of STM headquarters to denounce this preferential treatment, demand fair collective agreements and call for better government funding of the network—rather than favouring the private sector.

Examples of public transit subcontracted to private companies do not inspire confidence among transit workers. During the protest, the Réseau Express Métropolitain (REM) was repeatedly criticized for its inefficiency.