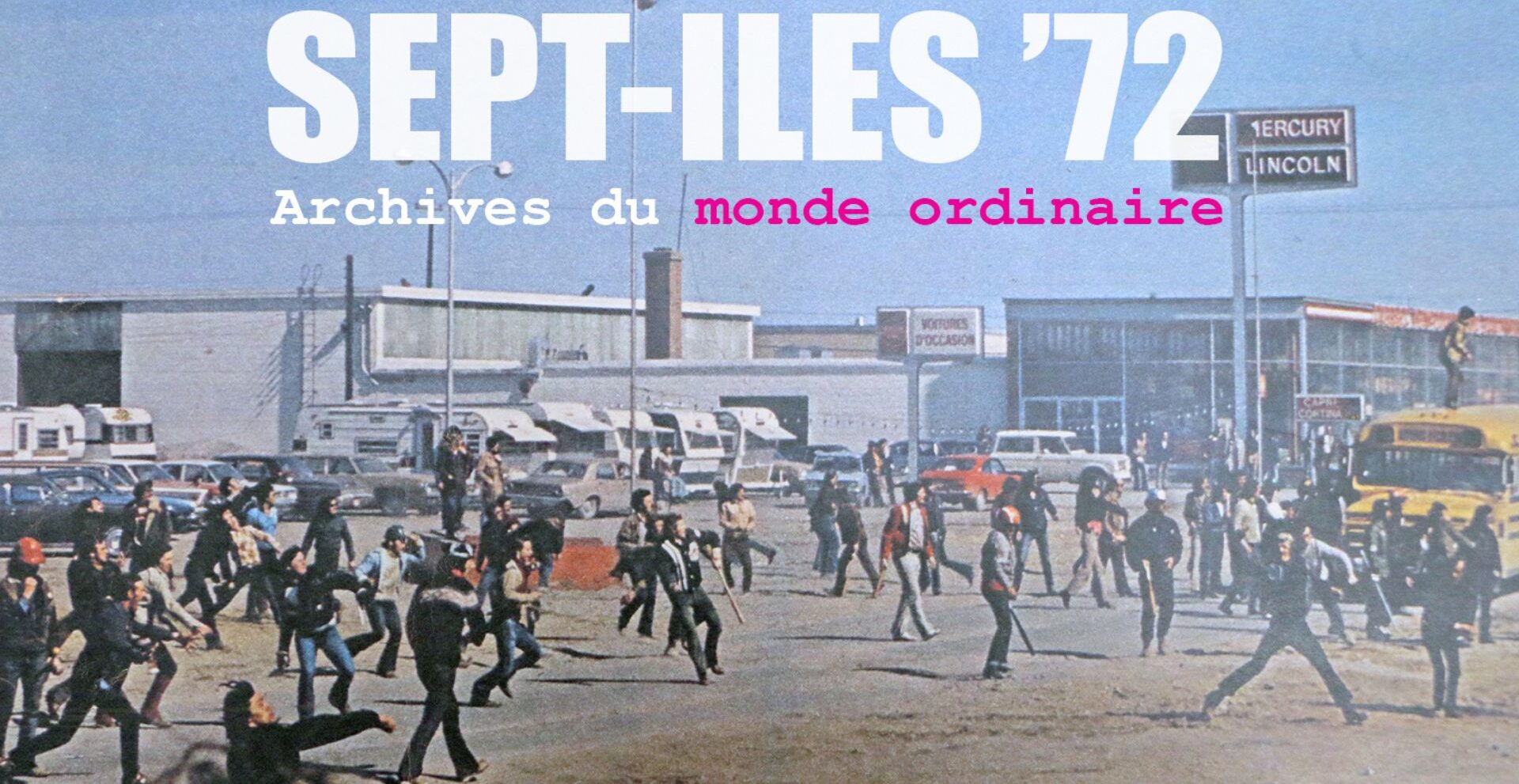

The documentary “Sept-Îles '72: Archives du monde ordinaire” (Sept-Îles '72: Archives of Ordinary People), shown during a special screening on June 5 in Montreal with its director Etienne Langlois, tells the captivating story of one of the most turbulent episodes in Quebec's working-class history. The film is based on a vast amount of archival footage, juxtaposed with images of Sept-Îles today, and on the testimony of several witnesses and authors of the workers' occupation of the city.

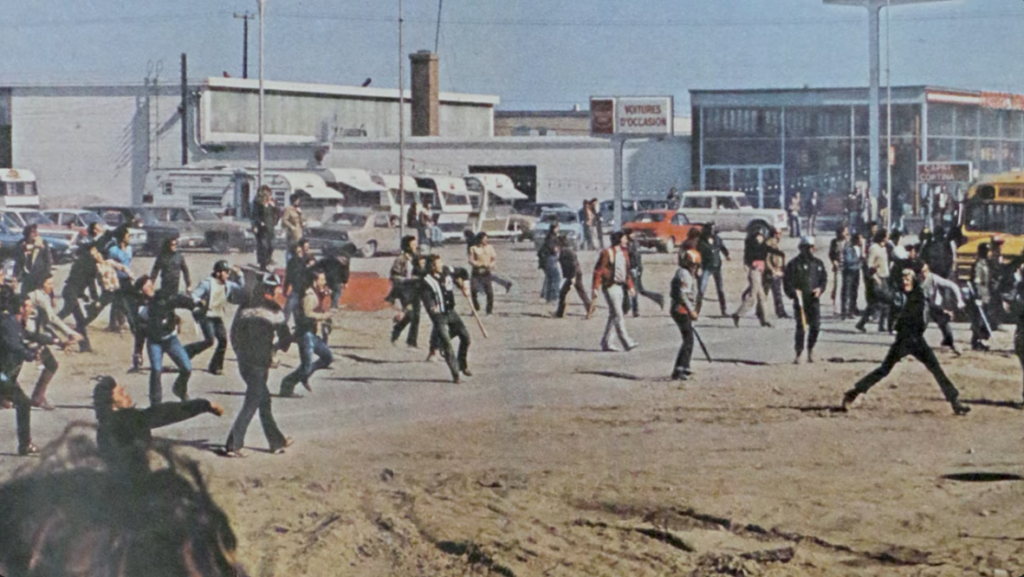

While acknowledging that the 1972 Common Front movement made power tremble across the province, the film attempts to explain why it was in this town on the North Shore of the St. Lawrence, home to some 15,000 people at the time, that the struggle took on such magnitude. Workers blocked all land and air access to the city, carried out walkouts in all industries, and took over the radio station—Sept-Îles was briefly taken over by the workers.

The documentary refuses to suggest that great moments of history are caused by the decisions of a handful of individuals and leaders greater than the mass. Instead, the story is told by workers, shop stewards, supporters of the strike movement and some of its opponents.

Among others, we meet several founding members of the Front des travailleurs unis (FTU), including Réjean Langlois, the director's father. The FTU, a non-union organization that defended the political interests of Sept-Îles workers, had some 800 members even before the '72 strike. In particular, the Front campaigned for affordable housing for workers at a time when the bourgeoisie was increasingly gaining a foothold on the North Shore.

In the years leading up to the 1972 Common Front, the FTU and the workers who were part of it became increasingly radicalized, partly as a result of repression of their activities by the police and local bosses. They increasingly advocated class struggle and opposition to capitalism, inviting the likes of Michel Chartrand to give speeches in their town. When the workers took control of the CKCN radio station, right in the middle of the occupation of the city, they broadcast anti-capitalist FTU texts alongside official union communiqués.

It's largely the prior existence of this organization that explains why it was in Sept-Îles that the movement gained such momentum. Many workers were already angry with employers and government when the Common Front strike was declared. They were “the first to go on strike and the last to return to work.”

The documentary also sheds light on the causes of the end of the city's working-class occupation. The car ramming attack that wounded over 30 demonstrators and killed young Hermann St-Gelais was the first major blow that slowed the movement, but it didn't stop it completely. It took a hundred riot police, the same number of arbitrary arrests, and a near-martial law throughout the city to bring the occupation to an end.

In short, it is through the accounts of the actors and witnesses to the Sept-Îles workers' insurrection that this film helps us understand how this kind of social explosion can be triggered and extinguished just as quickly. It also reminds us that behind this kind of great uprising, there is always a political context that has been bubbling away for a long time.