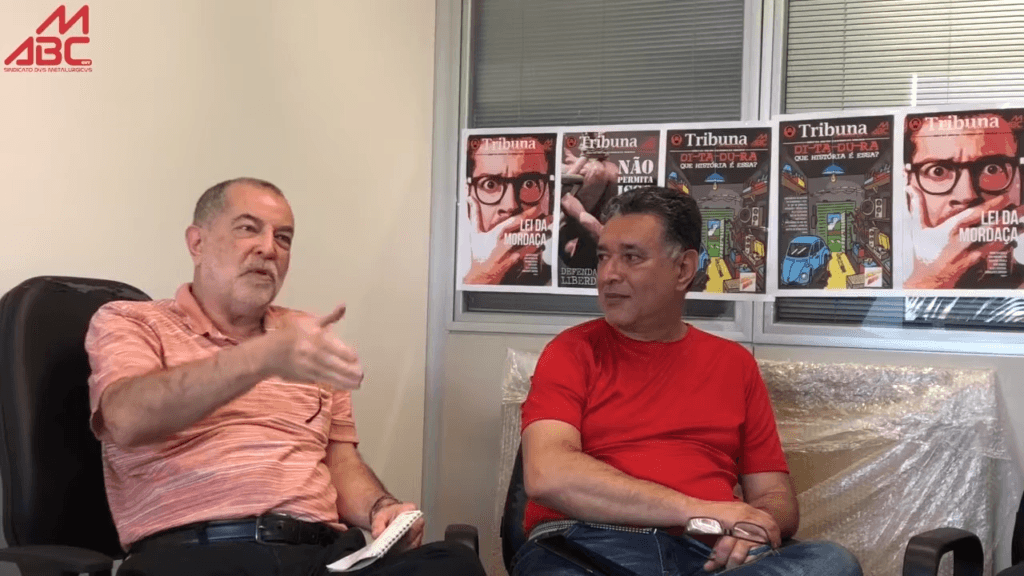

“We have a beautiful story here. A unique story, rooted in this region,” says Moisés Selerges Júnior, president of the Metalworkers’ Union of ABC (an association of cities south of São Paulo, Brazil) to The North Star. And he’s not wrong: the struggle against the military dictatorship that crushed the country from 1964 to 1985 is deeply tied to these thousands of workers.

But first, a bit of context: it’s the late 1950s. In Cuba, the US-backed military dictatorship of Batista has just fallen, overthrown by an army made up largely of peasants. The rest of Latin America starts to take note. Faced with the rise of peasant and worker movements, the United States (and, to a lesser extent, France) decide to intervene.

These powers begin supporting military coups across the region. To justify it, they claim they’re protecting people from a so-called authoritarian, oppressive communism. In reality, it’s the fascist military dictatorships they support that strip away rights, kill, and carry out mass repression.

That’s exactly what happened on March 31, 1964, in Brazil, with a coup led by Marshal Castelo Branco. This authoritarian regime ousted the elected government of João Goulart and would remain in place for twenty years… until it was deeply shaken by the metalworkers of the ABC.

The metalworkers and the dictatorship, a parallel story

The North Star traveled to São Bernardo do Campo, to the union headquarters, to understand why this region became the heart of such profound social change. The ABC includes cities like Santo André, São Bernardo do Campo, and São Caetano do Sul, as well as several others, including Diadema. Despite the name, the union mostly represents workers from São Bernardo and Diadema.

“The ABC region has always been very industrialized,” explains Moisés Selerges. “ABC metalworkers grew alongside the arrival of automakers in the area,” located between São Paulo and the state’s main port, Santos. “It all starts in the 1950s,” he adds, with the massive, rapid industrial expansion in São Bernardo and Diadema.

In May 1959, the Professional Association of Metalworkers was formed, at great cost: offices rented on credit, activists fired, persecution. Three months later, it became the Metalworkers’ Union of São Bernardo and Diadema. Even after the military dictatorship arrived in 1964, the union kept growing thanks to the industrial boom of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The metalworkers join the resistance

In its web series IA-5: What’s That All About?, the union gives the floor to several members who joined the resistance early on.

“From 1964 to 1968, people didn’t accept the situation,” recalls retired metalworker José Drummond. “For example, in Osasco [east of São Paulo], more than ten companies went on strike in mid-year, with lots of young people protesting in the streets. Meanwhile, factories were being occupied [by protesting workers].”

But “on December 13, 1968, [the military] staged a coup within the coup. They couldn’t stand the social unrest anymore, which was threatening to lead to new elections.” The dictatorship passed Institutional Act Number 5 (IA-5), which brutally tightened its grip:

- The president got full powers: he could shut down Congress and state assemblies, rule by decree, and change the Constitution.

- Censorship spread everywhere: newspapers shut down, political meetings banned, curfews imposed, arrests without trial.

- The regime could remove elected officials and suspend anyone’s political rights.

That’s when Drummond got involved in the union, and by extension, in politics. “After 1968, I went underground because it was impossible to do politics openly like we can today. The city was under heavy surveillance; we were spied on at home, and every visitor had to be registered.”

Like him, many union members joined the underground resistance. A plaque at the union’s Diadema offices reads:

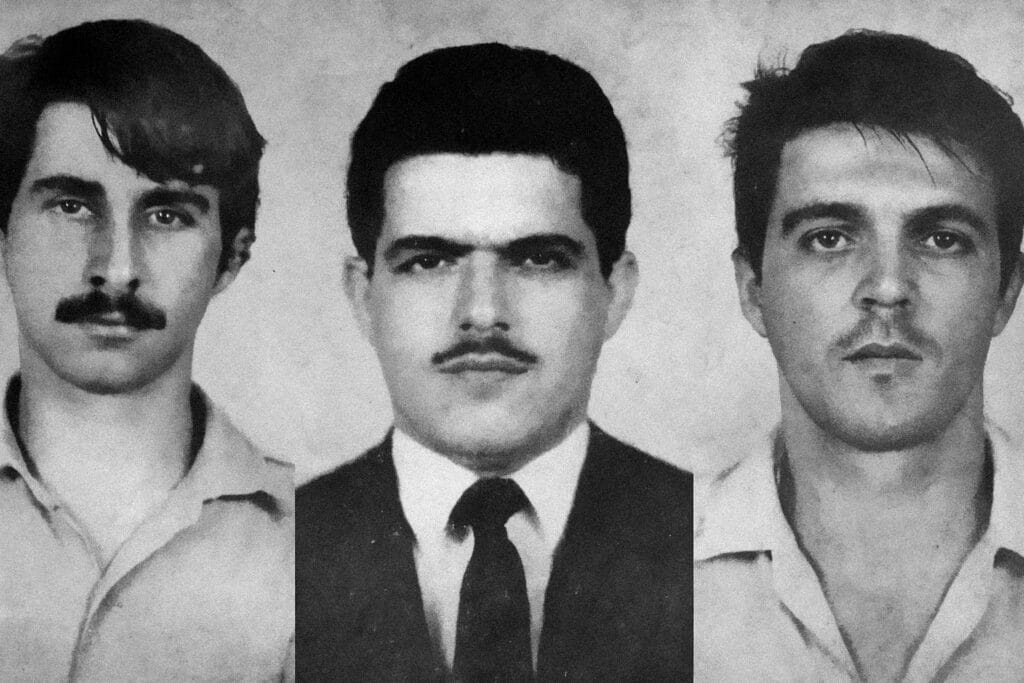

“Right after the coup, the regime unleashed its repressive machine on the workers’ movement. Hundreds of trade unionists were fired and imprisoned. Many were tortured, and some murdered. Among them were Aderval Alves Coqueiro and the three Carvalho brothers: Joel, Daniel, and Devanir—true representatives of the working class who gave their lives for a free and democratic Brazil.”

These four militants from Diadema helped found the union before joining the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB), then the Red Wing, and later the Tiradentes Revolutionary Movement. Through these groups, they carried out clandestine armed actions against the regime. All were arrested multiple times and later freed in prisoner exchanges so they could continue their fight. They were killed in the early 1970s by the dictatorship’s political police, the Department of Political and Social Order.

“I don’t regret anything, and I’d do it all again,” said Derly, one of the two surviving Carvalho brothers, in the web series.

A prelude to the fall of the regime

Diadema was also the scene of a key event that left a deep mark and inspired a new generation of resistance fighters, who played a major role in bringing down the dictatorship between 1979 and 1985.

“In Diadema, Carlos Marighella made a statement broadcast across Brazil on Radio Nacional Paulista,” recounts Moisés Selerges Júnior. Marighella and his group, the National Liberation Action, broke into “the radio station and delivered this call [to overthrow the regime] before the military realized what was happening.”

“Marighella became an iconic figure in Brazil. The Araguaia guerrilla [led by the PCdoB between 1967 and 1974] also played a crucial role. This struggle must always be remembered. That’s why we have this tribute at our Diadema offices.”

These battles laid the groundwork for what came next. The pressure from activists and guerrillas forced Ernesto Geisel, dictator from 1974 to 1979, to slightly liberalize society. This opening made possible a more open resistance, with the ABC Metalworkers’ Union playing a key role.

“You’re not going to win right away. You win little by little, by fighting, by claiming rights. You need perseverance in the struggle. That’s why this tribute in Diadema is so important.”

Moisés Selerges concludes: “Those who fought before us did so to deliver a better, fairer society to our generation. Now it’s our turn to work so we can hand something better to the next generation. That’s why those who came before deserve our tribute.”

Next article: How Did Brazilian Metalworkers Bring Down a Dictatorship? (2/3)