On October 9, over 25,000 health care workers unionized with CUPE and MGEU in Winnipeg and the southern surrounding regions secured a tentative agreement just hours before they were set to hit the picket line.

The agreement, which membership voted to ratify on October 18, sees flat increases of $3.00 and $2.65 per hour for each bargaining pool on top of a 12.25% wage increase over the four-year agreement. This amounts to an average wage increase of 27% over the next four years.

"A Slap in the Face"

The unions had to wait over a month before receiving the new agreement after voting down the province's first proposal for a pay increase of only 2.5% and 3.6% over four years.

Dieth, a health care aide with CUPE 204, described this first deal as "a slap in the face." He added, "Health care workers [in Manitoba] are one of the lowest-paying jobs in all health care in Canada. [Under the new agreement] health care workers won't be the lowest-paying job anymore."

The rejected offer also included a reduction in weekend bonuses from $8.00 per hour to $5.75 per hour for home care workers. Home care workers are only paid a base rate of $17.00 per hour for their physical and sometimes dangerous work. Taking into account the rate of inflation, this would have resulted in an overall pay cut, even when accounting for the base wage increase over the four-year contract.

Due to the nature of the job, many home care workers have to own vehicles to reach their clients, adding to their economic burden under an already rapidly rising cost of living.

Many health care aides have also had to deal with double shifts. While the employer cannot mandate workers to do overtime, Jackson, a health care aide, described how the employer uses the compassion that workers have for their clients as a way to pressure them into working overtime to fill vacancies:

"We all have a heart. Nobody's going to just want to walk off the job, leaving nobody else there. So it's kind of like a guilt trip."

Resolved to Fight

Jackson described a sense of resolve among the workers as the strike deadline approached.

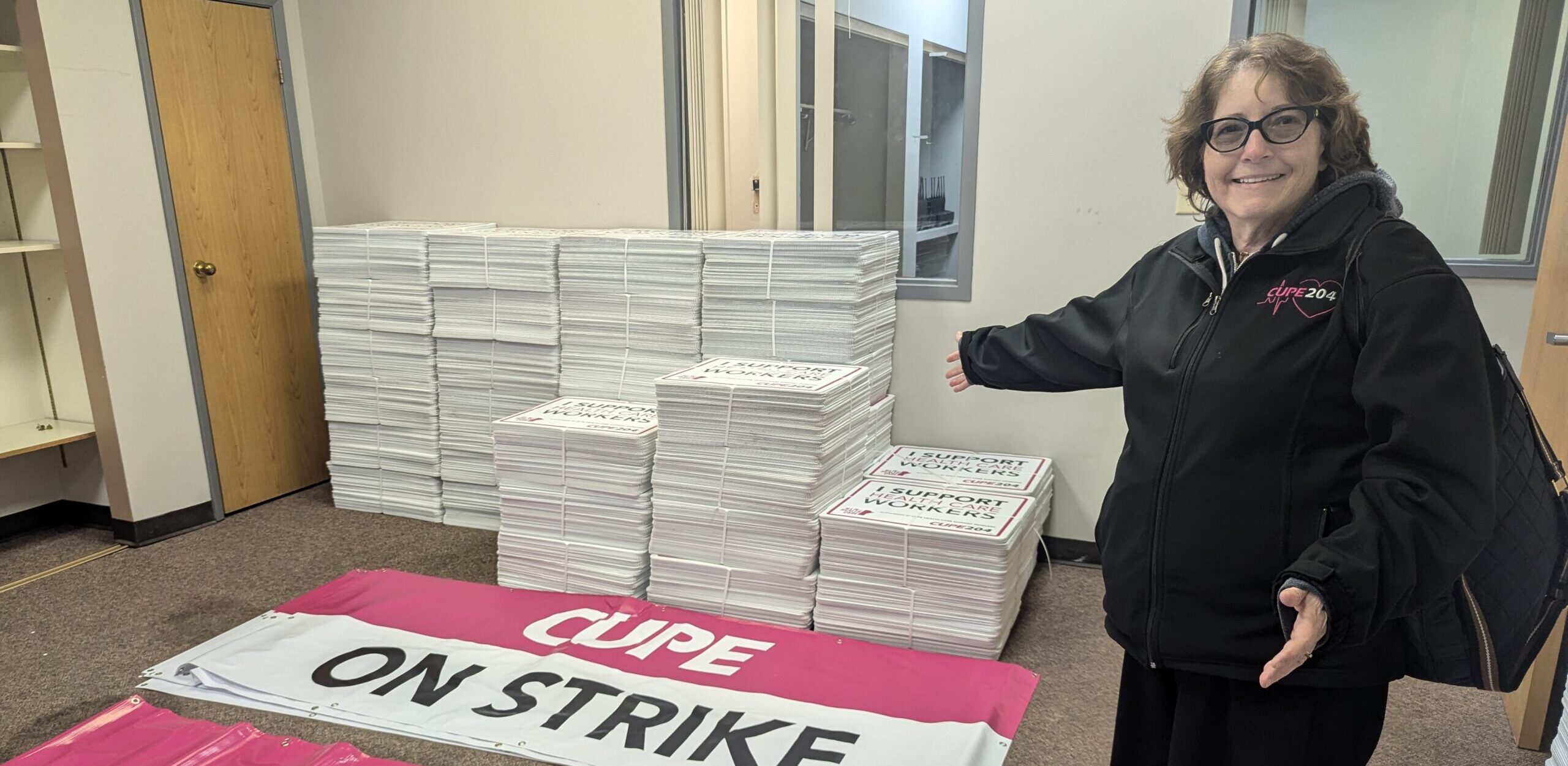

"We were prepared. It wouldn't have been looking good for the employer if 25,000 people went on strike," he told The North Star. “We were all ready to fight for better wages alongside having [...] public support with the 15,000 email signatures that we had.”

The total number of workers in bargaining units would have made this the second-largest labour action in the province after the historic 1919 Winnipeg general strike.

However, health care workers' designation as essential workers severely curtails their strike power, as only 30% of the workforce would have been able to participate in a strike action at any given time.

Furthermore, the province uses non-union contract workers from for-profit agencies for its home care program. These workers are brought in to fill gaps in the health care system.

Jackson told The North Star, “We should rely more on our public workers who work in the facility every day who have these relationships with the residents rather than the agency workers who are paid more. They can fulfill the holes in our system temporarily, but it doesn't solve any of the long-term problems that are occurring in the facilities.”

Building Confidence

Both Jackson and Dieth referenced the Manitoba Nurses Union as a source of inspiration. In 2021, Manitoba nurses voted overwhelmingly in support of a strike.

Dieth told The North Star, "The health care workers realized that the nurses stood up for what they believed and what they deserved." Jackson further explained, "Nurses and the doctors recently, they all got pretty generous wage increases. And the health care aides, we are the safety net of the facilities. We are the bottom line."

He added, "If the health care aides are locked out of the job, there would be no resident care. So if everybody else is getting generous wage increases and collective agreements that they are happy with, why not the health care aides?"

Jackson described the experience of preparing to picket: "[It] brought people together. They really needed to find the people who were willing to answer questions or willing to go back and forth with our union rep, so people came to me, came to other people who were vocal, asked lots of questions, and we got each other's phone numbers."

Referring to workers coming together and talking in the lead up to the strike, Dieth told us, “It's like a revelation where those who are deaf can now hear, and now they are hearing everything.”

He further added, "Without the workers, WRHA [Winnipeg Regional Health Authority] is nothing."