“The United States appear to be destined by Providence to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.” When Simón Bolívar wrote those words after freeing South America from Spain, he surely hoped it wouldn’t become a prophecy. Unfortunately for him, the quote remains strikingly relevant today, as the United States appears ready to plunge the region into armed conflict.

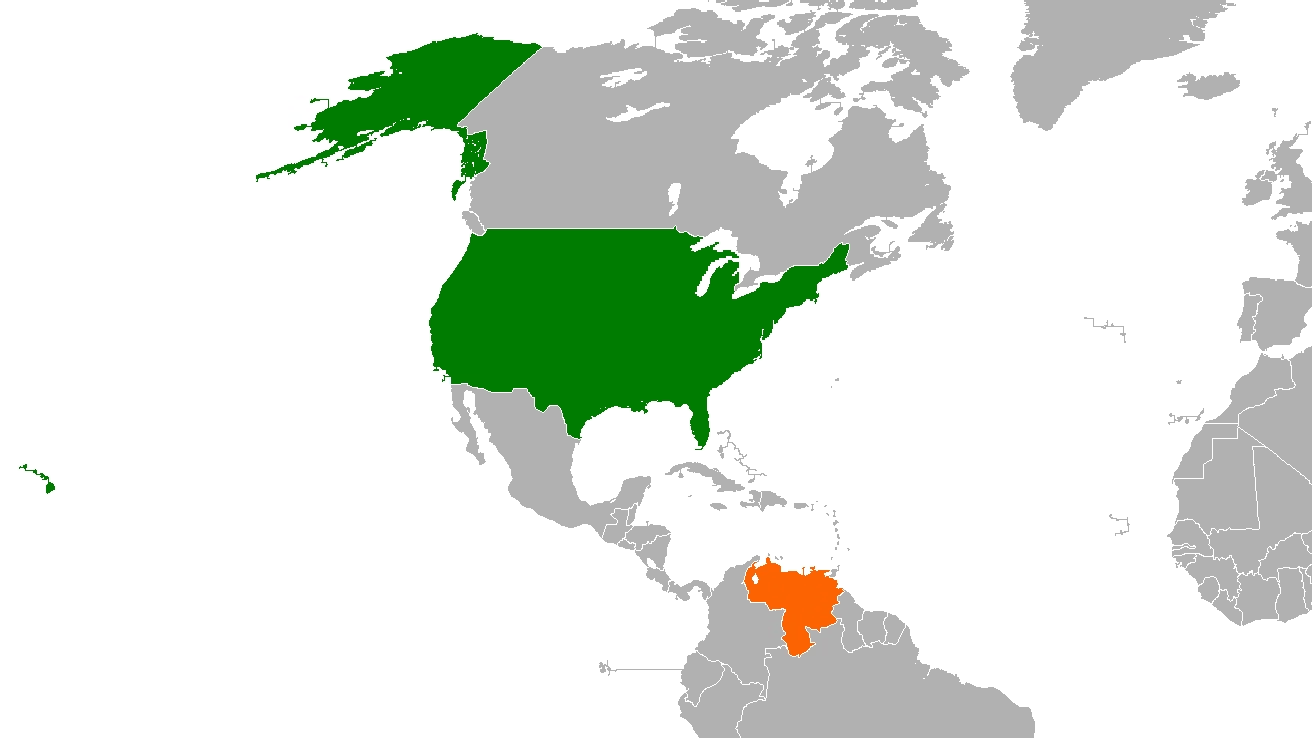

In 2014, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States declared the region a “zone of peace.” Despite that, Washington is now deploying more than 10,000 troops and around a dozen warships off Venezuela, including the largest aircraft carrier in the world. The United States presents this operation as a fight against drug trafficking, but few international observers seem convinced.

And for good reason: it is the largest U.S. military mobilization in Latin America since the 1989 invasion of Panama. In recent months, the U.S. has also carried out systematic extrajudicial executions by blowing up boats in the Caribbean (an illegal act, according to the UN). Nothing indicates the victims had any link to drug trafficking… and the Pentagon does not seem to know either.

Concerns deepened when Alvin Holsey, commander of “SouthCom”, abruptly resigned. He was in charge of all American military operations in the region. Many speculate he refused to repeat what happened in 2003, when Washington invented a pretext to invade Iraq by accusing Saddam Hussein of possessing weapons of mass destruction.

Drug trafficking as a pretext?

Everyone knows fentanyl comes almost entirely from Mexico. Both the UN’s World Drug Report and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration say so.

As for cocaine, three countries produce the vast majority: Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. Around 75% of the trafficking moves through the Pacific toward Mexico, where cartels bring it into the U.S. through the border. According to the same reports, only about 8% moves through the Caribbean, and even less through Venezuela.

So how to explain Washington’s aggressive stance? The history of the 20th century suggests the U.S. is trying to restore its declining hegemony in what it sees as its “backyard.”

Since the start of the 21st century, Cuba and Venezuela have been Washington’s main rivals in the region. With the “Bolivarian Revolution,” Venezuela took the lead in counterbalancing U.S. influence, backed closely by Cuba. Facing American hostility, both countries moved closer to China and Russia, the main challengers to U.S. global power.

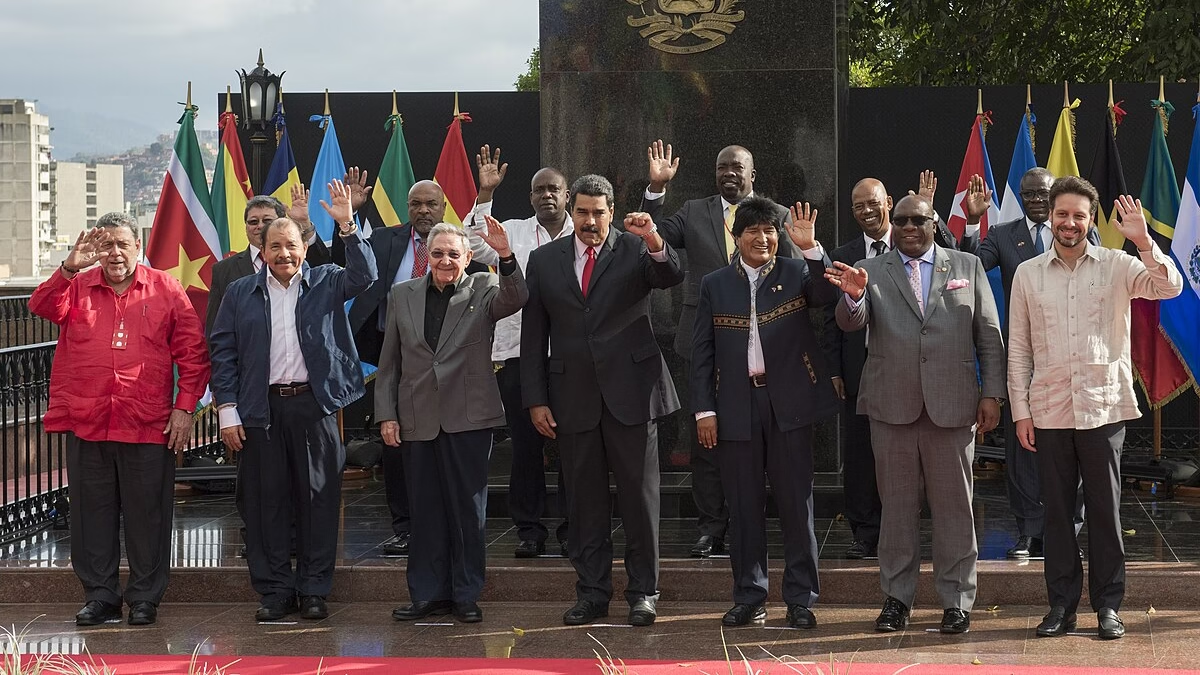

Two regional initiatives also challenge U.S. influence. The first is CELAC, created as an alternative to the Organization of American States, widely criticized for aligning itself with Washington. CELAC includes all Latin American and Caribbean countries, excluding the U.S. and Canada.

The second is ALBA-TCP, an alliance with an anti-imperialist orientation led by Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua, along with several Caribbean states. It seeks deeper political and economic integration among its members.

Cuba and Venezuela also maintain close ties with Russia, alongside their growing partnerships with China. For the 80th anniversary of the Soviet victory in WW2, they were among the few Latin American states attending military parades. Cuba’s president Miguel Díaz-Canel was the only regional head of state present at both the Russian and Chinese ceremonies, while Nicolás Maduro attended in Moscow.

Russia is a major political, military and economic partner for both countries. China’s role has expanded even more: trade with Latin America grew from $12 billion in 2000 to $518 billion in 2024, making Beijing the region’s leading trading partner.

Even without formal military alliances, China maintains strong economic, political and ideological links with Cuba and Venezuela, giving it a solid foothold in the region. It has also become the main buyer of Venezuelan oil since U.S. sanctions were imposed.

An old pattern

The U.S. has long viewed Cuba and Venezuela as obstacles to its regional influence and has sought to curb their power. Cuba is the main target of the National Endowment for Democracy, a U.S.-funded organization that supports opposition groups and projects aimed at weakening targeted governments. It dedicates about $6.6 million a year to Cuba alone.

There is also the U.S. base in Guantánamo, denounced for decades as a violation of Cuban sovereignty, and an embargo condemned 33 years in a row at the UN. The embargo was tightened under Trump, with severe economic and social consequences.

Venezuela has also faced intense pressure for years. After the 2018 election, Washington recognized Juan Guaidó as leader of an “interim government,” then imposed sanctions estimated at more than $10 billion per year. These measures worsened an already deep crisis triggered by the 2014 collapse in oil prices, caused by U.S., Canadian and Saudi overproduction. Despite having the world’s largest oil reserves, Venezuela saw its revenues collapse by 80%.

In 2024, the United States recognized the opposition led by María Corina Machado and Edmundo González as the winners of Venezuela’s election. The Maduro government (weakened but still in place) remained in power, angering Trump, who claimed he “would’ve gotten all that oil” had he stayed in office.

Under Trump’s second term, the strategy of isolating these governments intensified. The appointment of Marco Rubio as Secretary of State reinforced this hardline approach. Rubio, the son of Cuban immigrants, is a fierce opponent of the governments of Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua, calling them “enemies of humanity.” He has recently toured the region to push Latin American governments to join Washington’s campaign of maximum pressure.

In this tense climate, the OAS announced it would exclude all three countries from the next Summit of the Americas in the Dominican Republic. Mexico and Colombia immediately declared they would boycott the event. At the same time, Washington is offering a $50 million reward for Maduro’s capture, and the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to opposition leader María Corina Machado. She is a strong supporter of the genocide in Palestine and an advocate of capitalist liberalism and major oligarchs.

The United States’ renewed aggressiveness in the region brings back dark memories: the 1915 occupation of Haiti, military interventions in Central America in the interests of United Fruit, U.S.-backed paramilitary campaigns in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, the invasion of Grenada in 1983 and the invasion of Panama in 1989. Today, many governments fear a new escalation.

And for many in the Caribbean, the moment evokes the famous warning from Rubén Blades’ song “Tiburón,” a symbol of resistance to foreign interference: “If you see him coming, [bring a] stick to the shark!”

Be part of the conversation!

Only subscribers can comment. Subscribe to The North Star to join the conversation under our articles with our journalists and fellow community members. If you’re already subscribed, log in.