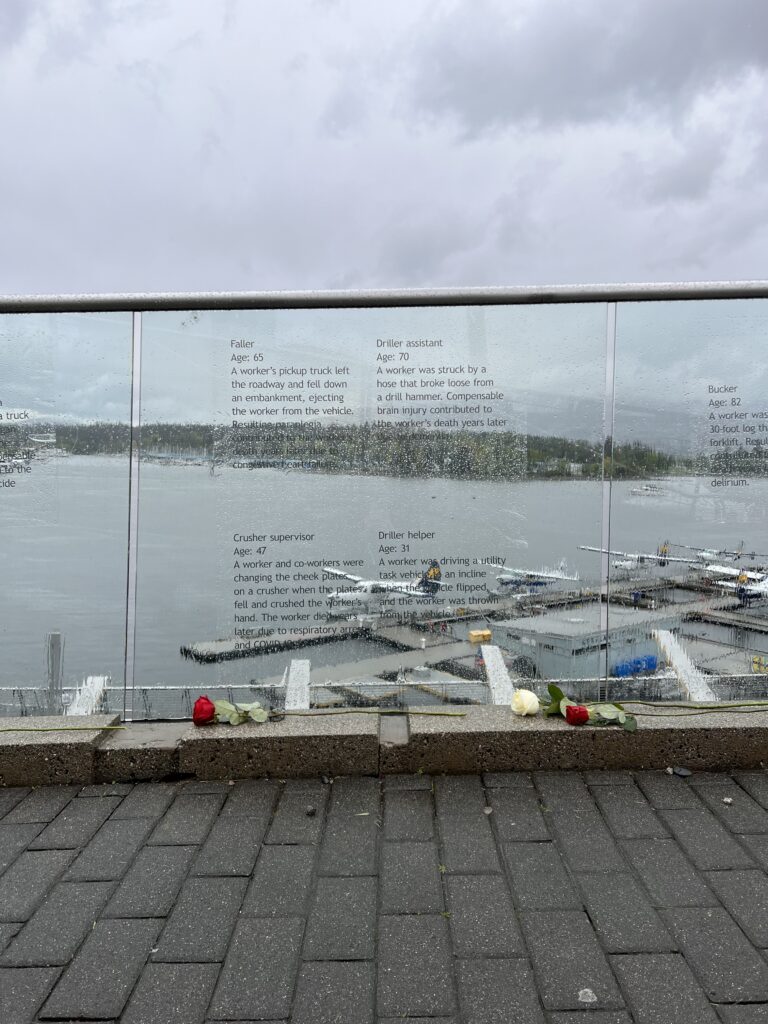

On April 28, conflicting views on workplace safety took centre stage at a National Day of Mourning event at Jack Poole Plaza in Vancouver. The National Day of Mourning, also known as Workers’ Mourning Day, is an annual observance commemorating workers who have been killed, injured or made ill by their jobs. The event organized by the B.C. Federation of Labour, the Business Council of British Columbia, the Vancouver and District Labour Council and WorkSafeBC exposed the rift between workers on the one hand, and their bosses and the government on the other, including NDP Premier David Eby, who was in attendance.

“Employers fight us at every turn to change the rules in this country. We won’t be standing shoulder-to-shoulder with employers on April 28 anymore,” said International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) President Rob Ashton, who spoke to North Star at the event.

“[The ILWU] passed a resolution last week never to attend this event again. We’re going to do our own thing because one day out of the year, April 28, we don’t believe belongs to the employers. It belongs to the workers because it is the employers who are killing our people.”

Speaking to the gathering, Bea Bruske, President of the Canadian Labour Congress stated that “almost 1,000 workers die every single year because of an incident that has happened at work.” According to the Ontario Federation of Labour, this figure is underestimated and could be much higher.

Bruske continued: “Whether it’s an accident, a toxic exposure, a fatal injury, these workers’ lives were cut short because of something that happened at their job.” Emphasizing the increasing casualty numbers in Canada, she noted that “there were over 300,000 accepted lost-time claims last year alone across the country, a sharp increase from the year before.”

One major gap in the safety of worksites is the regulation of cranes. The assembly and disassembly of tower cranes caused at least four unsafe incidents in Metro Vancouver since the beginning of the year. Yuridia Flores, a 41-year-old construction worker and mother of two, was killed in one such incident on February 21 while working on a multibillion-dollar development in the Oakridge neighbourhood of Vancouver.

According to WorkSafeBC, there were 22 incidents involving tower cranes between 2019 and 2023, one of which caused the deaths of five workers on a worksite in Kelowna in 2021.

Josh Towsley, a representative of the International Union of Operating Engineers, told the Vancouver Sun in late February that crews working around cranes and those doing the assembly and disassembly do not need certification. Some operators have a provisional licence, which in some cases only requires the operator to pass an online multiple-choice exam.

The site in Oakridge remains halted due to a stop-work order issued by WorkSafeBC. While the province has launched an investigation into the incident, Ashton emphasized the lack of sufficient funding to support investigations. “Government has to actually fund their investigation sites, and [have] properly trained investigators” to get casualties to trend downwards.

On the Day of Mourning, Premier David Eby expressed his gratitude to the unions for their “advocacy for prevention” of workplace accidents, but workers present felt that the province’s actions spoke louder than words.

“When a worker’s killed on the job, [the employers] shouldn’t [only] be slapped fines of $64,000 or, in the case of the two longshoremen that passed away recently, $250,000,” said Ashton, referring to a 2018 case at Neptune Terminals.

In that case, the company was found negligent in failing to ensure employee health and safety and was fined $250,000 for the death of 51-year-old Don Jantz. The company had been warned about the clips on a grate repeatedly coming loose and was repeatedly urged by engineers to have it replaced with a safer alternative before it gave way, resulting in the 17-meter fall that killed Jantz.

Everett Cummings, 44, who worked as a heavy-duty mechanic for Fraser Surrey Docks, died the same year as Jantz in a similarly avoidable incident when he was crushed by a lift truck he was servicing.

“When an employer is negligent, that employer has to go to jail,” said Ashton emphatically. “The provincial government [has] to make sure that the employer is punished properly. Until that day happens, workers are going to die on the job because there is no fear [on the part of] employers of any type of payback from anybody.”